A tale of two jails: considerations of memory and justice in a circular economy

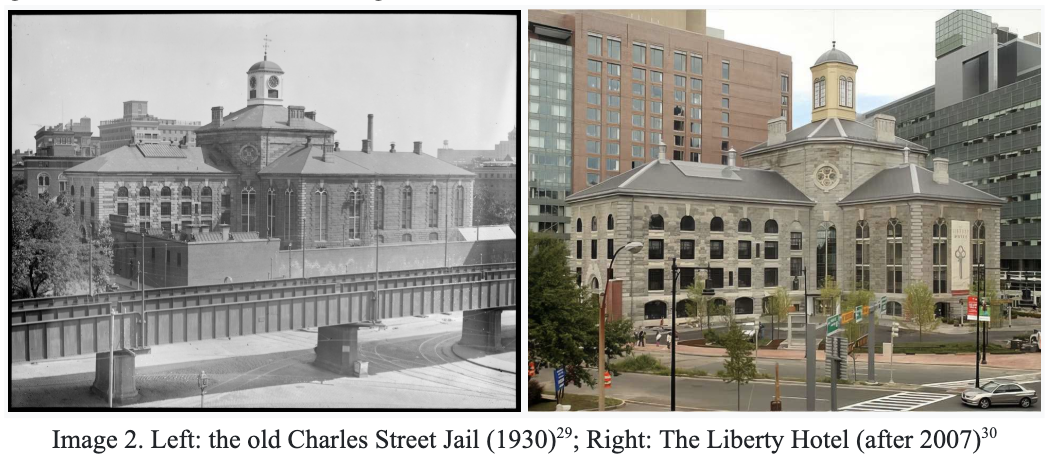

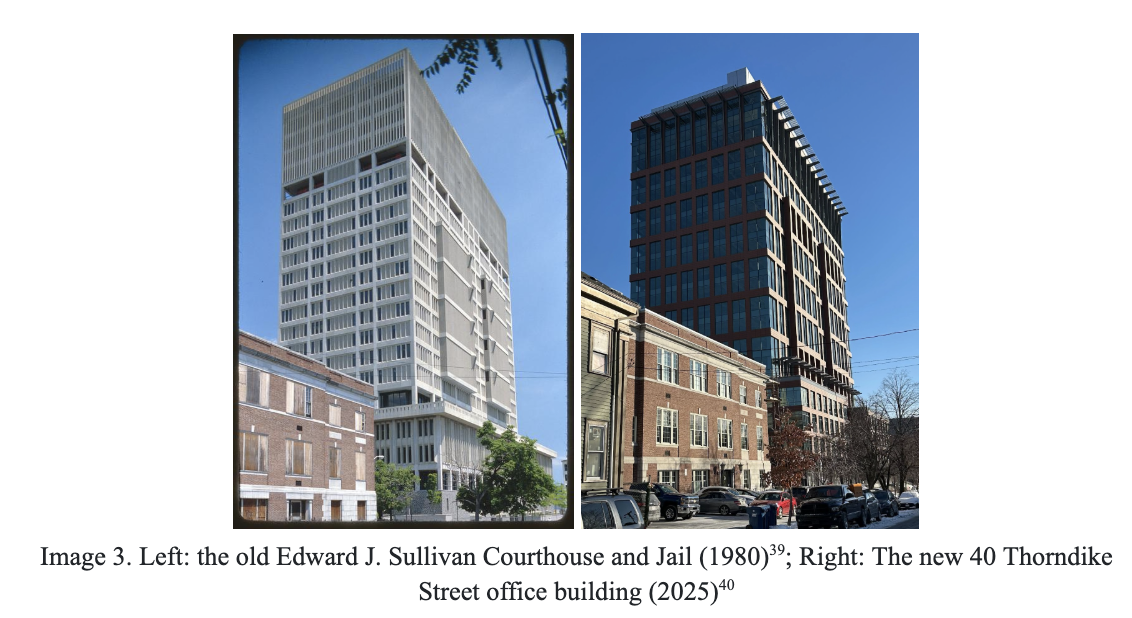

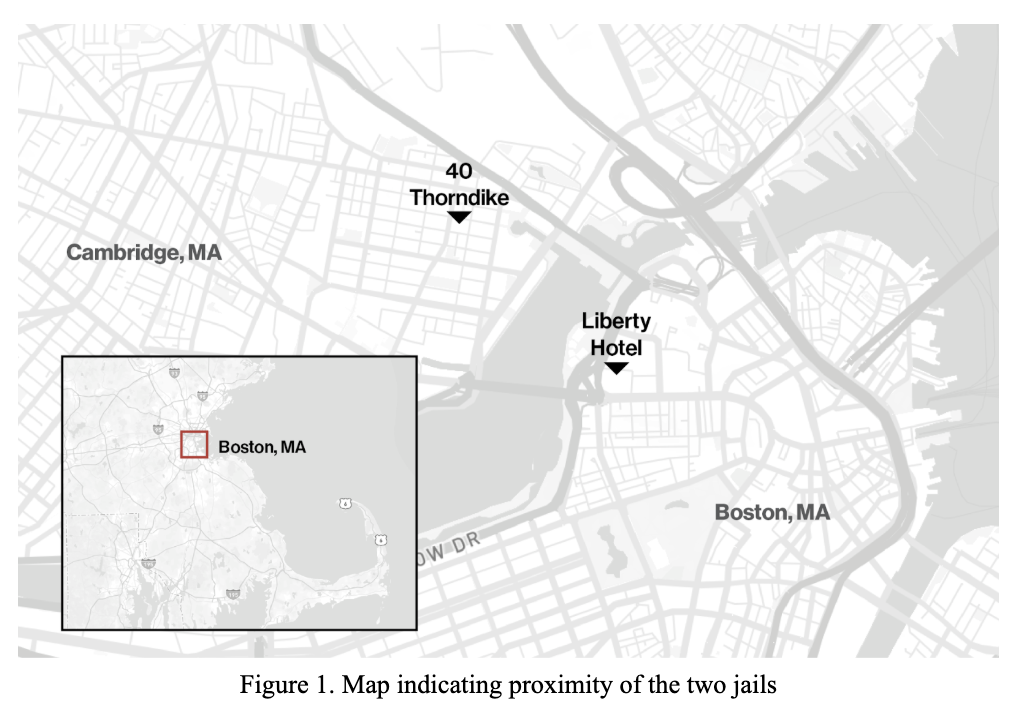

In 2002, Charles Street Jail in Boston, MA was converted into a luxury hotel. For its new developers, the building’s previous life was a selling point, hence the hotel’s name: Liberty. But less than two miles away, just across the Charles River, the former Middlesex County Edward J. Sullivan Courthouse and Jail, now known as 40 Thorndike, told a different story. Recently converted into a mixed-use development amidst a rapidly developing innovation hub, nowhere in its promotion did it mention its former identity.

Adaptive reuse has been identified as a beneficial circular strategy for the built environment, particularly in post-industrial cities where the existence of factories, warehouses, and military posts have created enough space and structural load capacity — as well as building materials that have been deemed culturally valuable. However, in the context of the American carceral system and trends in prison boom and bust building cycles, designers must consider more than just economic potential, material capacity, and carbon emissions when recovering these buildings. This paper compares the conversion processes and completed redesigns of the Liberty Hotel and 40 Thorndike in order to scrutinize which factors must be addressed when adapting spaces with traumatic histories. This paper posits that in the recovery of buildings with troubled pasts, only accounting for the environmental incentives divorced from questions of memory and injustice falls short for successful implementations of a truly sustainable model for architecture.